What Ethical Questions Come Into Play When Discussing Continued Global Climate Change in the Future

"An ethically defensible decision is one that you can live with and for which you are able to provide a reasonable, ethics-based rationale to observers."

An ethical decision is one that we can defend with justification, that is, being able to explain how we reach the decision (i.e., the process) and why it is the most optimal decision (i.e., the principles). In public relations, ethics is a precursor to long-term organization-public relationships that ultimately contribute to organizational effectiveness. But the increasingly global, interdisciplinary and collaborative environment increases the unknowns associated with the ethical practice of public relations.

In a 2008 Bloomberg article written by Professor Bill George of Harvard University, he argued that "To build a truly great, global business, business leaders need to adopt a global standard of ethical practices." As globalization expands the challenge of ethical conflicts, the adoption of one global standard of ethical practices could help organizations justify the decisions they make without having to attend to the differences among various markets. On the other hand, there are problems associated with adopting one standard when there are "multiple and competing constructions of the good." There could be ethical problems associated with the construction of a global standard of ethical decisions. For example, what principles and processes do we construct this standard?

Ethics are commonly known as "rules or principles that can be used to solve problems in which morals and values are in question." Ethics guides us in determining what is right and wrong (i.e., morals) and helps us decide what is important (i.e., values). Because public relations practitioners are the boundary spanners between organizations and their publics, they are entrusted with the authority to make decisions about how to go about co-orienting between organizations and their publics to best build and maintain mutually beneficial relationships between the two. Yet, when practicing public relations in a global context, our understanding and application of ethics also ought to be put in the global context. "Public relations practice has globalized; it is time that we globalize our conceptualizations and reflect on the evidence and use our knowledge to ensure that public relations practice contributes even more toward the development of the world."

Challenges for Ethics in a Global Context

While public relations ethics are closely linked to the cultural and social environments, conceptualizing ethics in a global context could be challenging for the following reasons:

- Polarizations between local and global: The adoption of universal frameworks in conceptualizing global ethics is often resisted. Western imperialism is criticized for using international principles to rationalize the use of universal frameworks. Advocating for the global is considered another attempt to reproduce the imperialistic normative framework as a model for enhancing global and moral acceptance for Western imperialism. On the other hand, its counter-force advocates the use of cultural relativism. But this is also criticized for not addressing the problem that the interconnectedness of people and thus, the interconnectedness of problems, requires ethics to be applied transnationally.

- Power in the development of global ethics: In spite of the polarization, there is a need to recognize the capacity to build universal or common understanding and logical reasoning to solve transnationally connected problems. It is true that ethics, as a study of moral values of human conduct, of rules and principles that govern it, can be influenced by social, religious, civic and cultural factors. Because the development of global ethics is also largely driven by the political, social and economic trends of globalization, one must acknowledge that power could come into play when conceptualizing ethics in a global context.

- Defining global ethics: The increasing global interconnectedness and interdependence has given rise to the discussion on global ethics. The focus of conceptualizing ethics in a global context should center on "seeking reasonable and responsible agreement on global problems, agreement based on possibly diverse moral grounds." Yet, one major challenge is to determine what the boundaries are and what should be included and excluded. It is not just about adopting universal values applicable to all, but acknowledging globally connected obligations and responsibilities.

- Defining global publics: In addition to acknowledging global interconnectedness, the approach to global ethics must also acknowledge how this interconnection could cause global problems that require practitioners to consider how to go about solving the problems, why and by whom. Equal consideration should be given to all global publics concerned. The adoption of a global ethical framework is not justifiable if the values of only a few global publics are considered. Global inclusivity (i.e., considering everyone's values and moral thinking) and global solidarity (i.e., showing equal concern for everyone's well-being) should be considered when approaching ethics in a global context.

- Unequally shared global risk: Risk is shared in the global society – a future challenge is to connect political decisions with morality and connect rights with responsibilities. The approach to global ethics should respond to both nations' self-interests and universal moral values. But in this respect, there is a hierarchy of values because global ethical principles contradict each other. Universal values are often brought in to justify worldwide responsibility for individual and institutional actions. Yet, it is a challenge to create a shared set of values accepted by actors around the world when the risk of their actions is not equally shared.

Building a culturally sensitive universal framework of global ethics? Whether it is possible to accommodate a diversity of practices within a culturally sensitive universal framework is questioned. "A global ethicist, or someone who does global ethics, explores and usually assumes and defends a particular global normative framework which she then applies generally or to particular areas of concern." Because entities make actions for the sake of others elsewhere in the world which could harm them, the approach to global ethics should acknowledge the relations individuals have with other individuals in the world. This question should be raised: is the approach to global ethics developed based on some entities' or groups' norms and values in respect to the world or based on shared norms widely and universally held around the globe?

Challenges for Ethics in a Global Context (continued)

There are fundamental concerns associated with the definitions of global ethics (e.g., can a consensus ever be made?) and the principles of global ethics (e.g., what are the most important values?). It has been discussed over and over again that a rational basis for a universal standard of global ethics which attends to cultural differences should be developed based on dialogue, but how to go about doing it remains a holy grail. In a global world, decisions at any level could result in globally impactful outcomes, but the globalization of ethics requires incorporating how people understand their relations to the world and the shared norms supported by individuals and groups from diverse backgrounds.

Role of Societal Factors

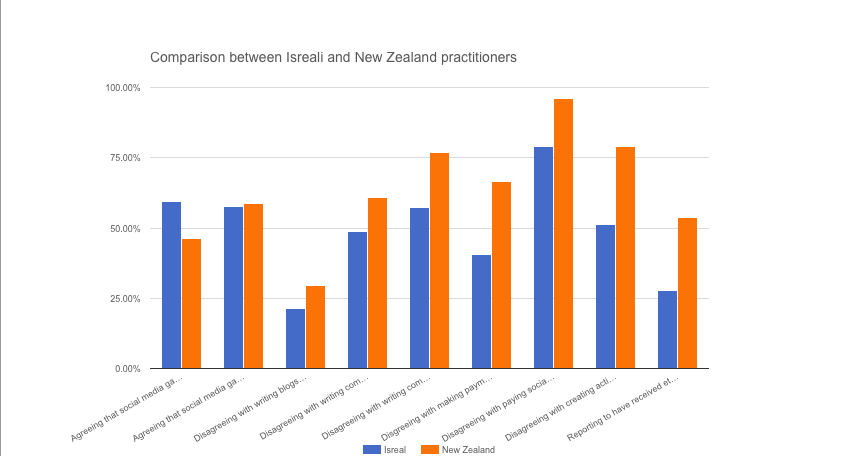

When practicing global public relations, practitioners are advised to pay attention to societal factors including political, cultural, economic and media conditions to understand how the public relations environment differs from each other. In response to calls for more cross-cultural studies in public relations, a survey was administered to compare practitioners' understanding of ethics on social media in Israel and New Zealand respectively. These findings were made:

- Control over distribution of messages: More practitioners in Israel (59 percent) than New Zealand (46 percent) agreed that social media gave them more control over the distribution of messages.

- Influencing management decisions: Practitioners in both Israel (57 percent) and New Zealand (58 percent) agreed that social media presented public relations with an opportunity to influence management toward making ethical decisions because of public scrutiny.

- Ghost-writing: More practitioners in New Zealand (29 percent) than Israel (21 percent) expressed reservations toward writing blogs on behalf of others.

- Writing fake comments: More practitioners in New Zealand (60 percent) than Israel (48 percent) disagreed with writing comments on social media without disclosing their real identity.

- Disclaimer about sponsor: More New Zealand (76 percent) than Israeli (57 percent) practitioners disagreed with writing comments on social media without a disclaimer about the sponsor.

- Paying bloggers: More practitioners in New Zealand (66 percent) disagreed with making payments to bloggers than Israel (40 percent).

- Paying for negative messages: 96 percent of New Zealand practitioners and 78 percent Israeli practitioners disagreed to paying for social media experts to spread negative messages about a competitor.

- Paying activist groups: 79 percent of New Zealand practitioners disagreed to creating activist groups to support their clients on social media (vs. 51 percent Israeli practitioners).

- Ethical training: Only 27 percent Israeli practitioners reported that they have received ethical training in communication on social media (vs. 53 percent).

The significantly lower scores that Israeli practitioners gave to the ethical statements in the study showed that they had lower levels of knowledge and commitment to ethical practices on social media. It is recommended that international indices be used to identify the similarities and differences in local and universal practices on ethics. The study proposes that in countries which enjoy more freedom, practitioners would be more conscious about ethics and would be less willing to accept unethical practices.

The above study indicates significant differences not only in terms of their approaches to ethical practices in public relations, but also their definitions of public relations (or how they have been going about practicing public relations). To some extent, the ethical standard in global public relations could also be challenged by the problems listed above, such as (a) assuming the utility of a universal standard, (b) disregarding specific societal factors driving the different principles and practices used, and (c) defining ethics as what should be done rather than what is accepted by the global community.

Approaches to Conceptualizations of Ethics in a Global Context

Although being ethical refers to making decisions that practitioners could justify, there could be multiple and contradictory sources of information which guide decision-making. And this could be even more complicated in the global context. Public relations practitioners have been asked to be internal activists in the organizations in which they work—that is, they should advocate for the interests of publics to influence organizational decision-making. They have been asked to be aware of the problems of the Western approach to ethics and to engage with local publics because Western practices might not be applicable to non-Western conditions (and vice versa). A study conducted on a global-local hand-washing campaign was designed based on the following assumptions:

- Multinational corporations' use of local-global integration: Multinational corporations would use global standardized worldwide development of best practices together with local responsiveness to customize practices to the local environment, organizational culture and people to achieve balanced public relations.

- Understanding culture: Understanding global publics requires knowing (a) the principles that guide what is valued in a culture, (b) the unwritten rules and guidelines that regulate conduct, and (c) the communication practices of the culture. Without understanding cultures, practitioners could not build emotional links with the local people who are affected by their practice.

- Culture-centered approach: It should begin with listening to subaltern global publics and using them as an agency to construct narratives which are useful to them.

The thematic analysis of the global-local hand-washing campaign run by the Global Public-Private Partnership made these findings:

- "Glocalization": The campaign ought to achieve consistency across all messages, goals and research methods worldwide. But they also tailored their media, strategies and tactics to different local publics.

- Understanding the marginalized: The campaigners gathered knowledge from those who lived in the communities, such as mothers and teachers through research. The researchers valued the indigenous knowledge from them although women remained under-valued in those communities. Also, the researchers hired were fluent in their local language, came from the same gender and spent time observing their domestic behaviors before conducting interviews about personal matters.

- Showing care is ethical: As a result of this research-driven campaign, the campaigners were informed by the real conditions facing the communities whose hand-washing behaviors needed to be altered. Their actively seeking to understand the communities and privileging local knowledge and experiences over their own assumptions was described as the portrayal of care and attentiveness which drives the ethical and effective dissemination of messages to the diverse global publics.

Levels of Ethical Behaviors

Donaldson and Dunfee have argued that either adopting host countries' ethical standards or exporting the values from the home countries to the host countries is equally problematic—photocopying values shows disrespect for local cultures. Therefore, they proposed a classification system to show different categories of global norms:

- Hypernorms: Norms which are accepted by all cultures and organizations.

- Consistent norms: Norms which are culturally specific, but consistent with hypernorms and other legitimate norms, such as organizational cultures.

- Moral free space: Norms which could be in tension with hypernorms, but are unique cultural beliefs.

- Illegitimate norms: Norms which are incompatible with hypernorms.

While public relations is commonly known for its unethical conduct, unethical behaviors should be understood at three levels: individual, organizational and national. "The question of ethical behaviour, from the level of the individual, through the totality of organizational manifestations to the level of national and international bodies, has become the number one issue on the global agenda."

At the same time, the model of ethical responsibility should also be understood at three levels:

- The causation of negative effects through human or organizational actions

- The presence of subjective factors held by individuals, and

- The set of values attributed to society.

While what society expects of organizations could affect the ethical norms that organizations impose on individual employees, organizational structures could also prevent individuals from taking responsibility for unethical actions. This is especially the case when individuals' actions are not attributed to their conscience but their perceptions of what is societally, professionally and organizationally accepted. As public relations practices transform to adapt to changes in economic, social, business and cultural conditions, the ethical values of the practice could also change that the work it does could change the complexity of the dynamics of interrelationships in the global context.

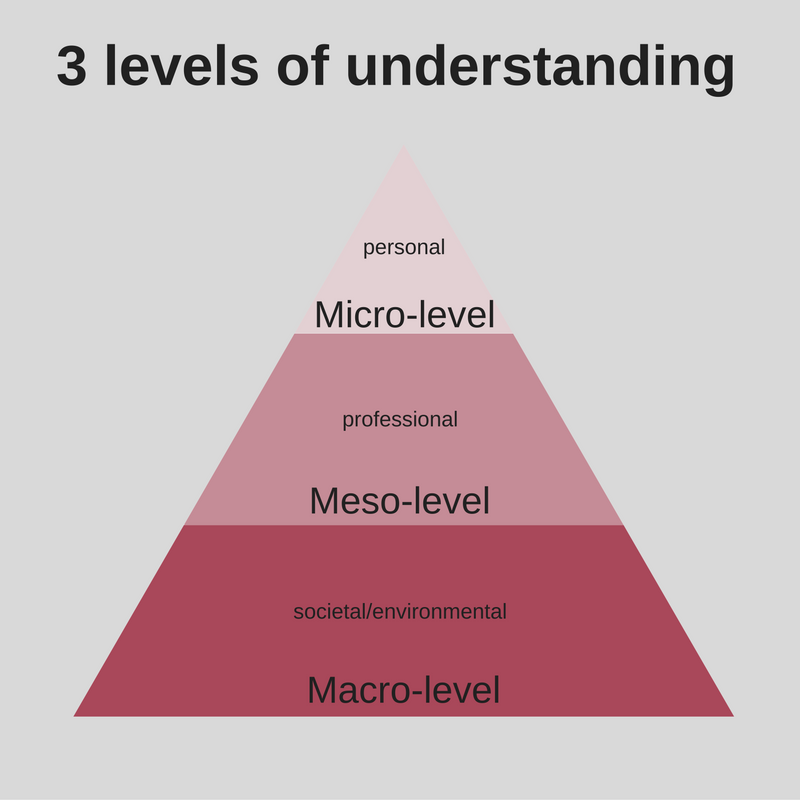

Tsetsura and Valentini produced a model which incorporated the significance of personal, professional and environmental values in affecting ethical judgements. They proposed a similar model of ethical judgement based on three levels:

- Micro-level: At the personal level, human values, including their preferable modes of behaviors and outcomes, would affect their views on how and what should be achieved through his or her behaviors.

- Meso-level: At the professional level, judgements could be affected by what guides their values in terms of what is seen as being accepted by the organizations and the professions they are in.

- Macro-level: At the societal/environmental level, one's personal networks, including family, friends and community would affect the extent to which practices are considered ethical or unethical. And such predispositions could be reinforced over time. In particular, country-specific factors, including changing political, economic and socio-cultural conditions, could influence the way public relations is practiced.

.png)

Based on these assumptions, a model is proposed to show that an individual's value system is made up of personal values, professional values and environmental values. At the same time, personal factors, including education, experiences, gender and background, and country-specific factors, including political system, economic system, and social-cultural system, are the external factors which could affect the values. There could be variations from one individual to another as individuals emphasize values from one level more than another.

Conclusion

There is no one single approach to the ethical practice of global public relations which will not receive criticisms—there are pros and cons with each of them. However, understanding how ethics are formed and expressed requires practitioners to understand how norms and values are formed at the individual, organizational and societal levels. It is easy to make an ethical decision when the norms in a foreign market happen to be the same as the norms in the domestic market. But when the two conflict, practitioners are likely to approach the ethical questions by considering what is ethically acceptable at the individual level, organizational level, societal level and global level (in that order). In Lesson #2, the ethical application of public segmentation and relationship management will be discussed in relation to global public relations.

Case Study: Mercedes-Benz

This case study was written based on Tan and Tan's study published in the Journal of Business Ethics in 2009.

Background

Ethics is vital to the practice of global public relations, but it is also "one of the greatest challenges facing practitioners in the 21st Century because it impacts on the management of strategic relationships within the complex dynamics and interrelationships of a global context."

In the Chinese market, foreign car brands have a competitive advantage over domestic car brands because of their being associated with luxury and novelty. Thus, they have experienced tremendous growth in the high-end market, especially after China entered the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 when the tariffs on imported cars were significantly reduced.

However, the strength of a strong brand being associated with luxury and novelty could also be its weakness—there are high expectations for their product quality and customer service in the minds of Chinese consumers.

Dilemma

In 2001, German auto-maker, Mercedes-Benz, was involved in a clash with the Wuhan Wild Animals Zoo when the zoo discovered problems with the quality and reliability of the vehicle. In December 2001, a Mercedes-Benz owned by the zoo was found to be dragging into the street by an ox. The act was considered a protest toward the problems with the vehicle's performance and quality, resulting in numerous costly repairs.

After numerous attempts to request Mercedes-Benz to replace the vehicle and cover the costs of the repairs, the zoo was dissatisfied that the company had not repaired the car like it would in the United States.

Similarly, in 2002, a Mercedes-Benz owner performed a public act of destruction after numerous attempts to repair the car. The quality problems of the vehicles resulted in the formation of an anti-Benz organization, Association of Victims of Benz Quality Problems. In other words, a public-initiated public relations (PPR) problem arose as publics formed into active and activist groups to collectively solve the problem.

Their problem recognition was high as a result of the gap between their expected state and their experiential state. The following factors contributed to the perpetration of the problem:

Discrepancy between U.S. and Chinese laws: The Chinese consumers heard that the U.S. had a law which would require the company to replace the defective car with a new car after the third repair. They felt discontent to have been treated differently.

Class action lawsuits not allowed in China: The Chinese government actively suppressed class action lawsuits because they could cause social instability. Thus, individual consumers were not protected by the legal system and had to use other means to have their problem resolved.

Expectation of the adoption of Western principles: Because Mercedes is a Western company, consumers expected that it would favor the "customer is always right" principle.

Course of Actions

After numerous attempts to repair their vehicles and negotiate with Mercedes-Benz, the issue was escalated into a crisis as consumers attributed Mercedes-Benz's lack of interests in resolving the matter as the result of "the arrogance of Western multinationals." Thus, they responded by smashing more cars which resulted in extensive media coverage and hostilities against the company.

Mercedes-Benz responded by:

Declining the request: It did not offer explanations for the malfunctions and attributed responsibility to consumers for their use of Grade 93 gasoline instead of the Grade 97 gasoline recommended. Chinese consumers responded by saying that it was not written in the manual in Chinese.

Reasserting consistency in customer service: In a statement published after a widely publicized event of car smashing, it claimed that it dealt with all reasonable concerns and issues in the same manner all over the world. Chinese consumers had claimed that the way Mercedes-Benz treated its Chinese consumers caused them to lose dignity.

Condemning publicized acts of car smashing: The company described the highly publicized acts of destruction as "unreasonable and senseless" and requested apology for the public defamation of their reputation. They even threatened to take legal actions against acts of consumer protests.

Consequences

The activation of public sentiment through consumers' smashing of their own cars showed that Chinese consumers were no longer seeking dialogue or negotiation. The issue became framed in the media as a matter of national dignity and resulted in Chinese consumers' gaining a new understanding of consumer rights and responsibility.

In 2008, when Mercedes-Benz discovered a manufacturing error in its vehicles, it announced a massive recall in China and established a hotline for consumers to report their concerns. Mercedes' announcement of product recall reflected its having learnt a lesson from its previous experiences.

Moral of the Story

Lesson #1 highlights the contestation of the adoption of a global vs. a local standard of ethical practices. It is problematic when there is a gap between Chinese consumers' expected state and experiential state. On one hand, Chinese consumers expected that foreign companies would adopt the same principles as they would in other markets. On the other hand, they experienced that foreign companies were just like domestic companies. Public relations, as a relationship building function, should recognize that publics have different expectations for local and global companies. Although country-specific factors, such as political system, economic system, culture, media system and level of advocacy, are relatively static, publics' expectations for companies could differ from one company to another. Instead of asking what country-specific factors should guide us in adopting one standard of ethical practices for one country, we should ask what standards are expected of my company.

Discussion Questions

- What are the ethical problems in this case?

- What are the global ethical problems present in this case?

- How was public relations practiced in this case?

- How should public relations be practiced in this case?

Lesson 1 Assessment

Source: https://www.pagecentertraining.psu.edu/public-relations-ethics/ethics-in-a-global-context/lesson-1-need-a-title/

0 Response to "What Ethical Questions Come Into Play When Discussing Continued Global Climate Change in the Future"

Post a Comment